More and more cervical fusion patients are reconsidering their treatment and questioning whether they really had to sacrifice their natural range of movement and flexibility for relief from chronic neck pain. As I see these patients come into my office, I wonder about the medical community that continues to rely on cervical spinal fusion as the ‘go-to’ solution.

According to federal data, the number of spinal fusions performed in the US has risen sixfold since 1990 to about 480,000 total fusions per year. It’s difficult to get an actual number for cervical fusions performed because of the statistical overlap covering all fusion types (cervical, lumbar, thoracic), but in my medical opinion, these numbers are hugely out of line. More than half of these patients should have never been fused.

One glimmer of light: patients are far more educated about their medical condition. More than ever before, they are knowledgeable about treatment options. Eleven years of clinical studies on artificial disc replacement (ADR) has not missed their attention. They are aware of the comparison data; that ADR provided at least equivalent and often superior outcomes for the treatment of degenerative cervical disc disease. Many patients who have had fusion are also aware that fusing more than two levels in the cervical spine often leads to a severely restrictive range of motion.

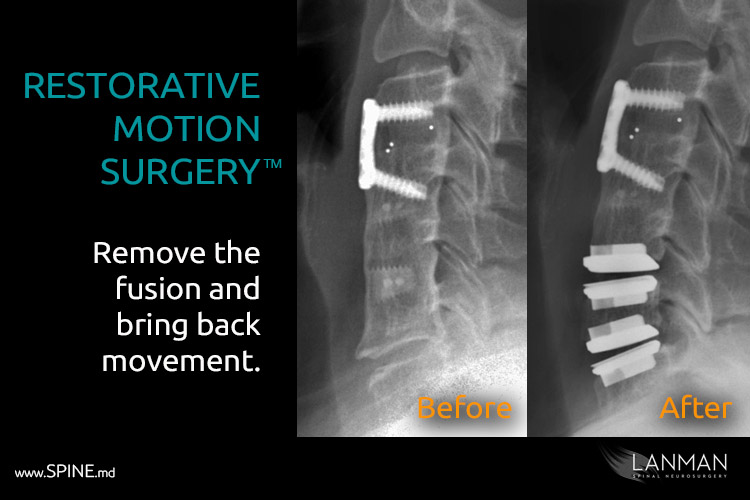

So, I wasn’t entirely surprised when a few years ago, patients started asking me about restorative motion surgery. This is a new technique of reversing cervical fusions and replacing them with artificial discs. The procedure enables patients to regain motion in the spine and to live an active and more functional lifestyle. In some cases, like mine, patients want to avoid additional fusions by adding artificial discs to adjacent levels instead of more fusions. Either way, this is the path to restorative motion.

I met a patient from Texas who already had a three-level cervical fusion from cervical 3 vertebrae to cervical 6 vertebrae. Predictably, another disc failed below the fusion at C6-C7. She wasn’t overly emotional, but I could tell she was in great pain and was genuinely concerned. Of course, she was: fusing C6-C7 would have wholly immobilized her neck. She was an avid golfer, had a very active lifestyle, and too young to be looking at this kind of situation.

After some reading, she sought me out for a second consultation. On our first meeting, she opened with a question, “Can you save my neck?”

I suppressed a gut reaction to get on my soapbox and share my opinions about fusion – the fact that it IS outdated – outmoded – and entirely unnecessary. Instead, I clicked into my clinical mode as a research clinician, board-certified neurosurgery specialist with more than 25 years of experience. I was no longer a clinical advocate; I was her doctor and a fellow patient.

We spent a lot of time talking. Golfing was her life, but she also led a very active social and family life. Her burning question was about the herniated C6-7 disc and whether she could have an artificial one instead of fusion. She also wanted to know if one or more of the previous cervical fusions could be replaced with additional artificial discs. All good questions.

My initial assessment confirmed a severely herniated disc at C6-C7, and that she was a good candidate for cervical disc replacement. Then I began my assessment to remove one or more fusion (C6-5/C5-4/C4-3). I was guided by the knowledge that by revising even just one of the fusions, she’d regain almost 35% of her original natural range of motion (turning, twisting, bending) in the cervical spine. However, there could be some complications if the facet joints (the bony extensions of the vertebrae) were either removed or fused.

A CT scan revealed that she had enough open facet joints where I could remove one level fusion by drilling it out and replacing it with an artificial disc. As long as the facet joints could support normal motion, she would recover from surgery with less pain and greater flexibility. I further explained that this was an “off-label” procedure. While not expressly approved by the FDA, it is not prohibited. It opens a way for surgeons, such as myself, to customize treatment for unique situations. It is also entirely appropriate considering my background as a research clinician.

She was very eager to do this and agreed. The surgery was a success, and her post-op experience was complication-free. She was up and out of bed within days. Instead of having FOUR cervical fusions (three existing plus a new one), she only has two fusions and two artificial discs. Moreover, she regained motion that the previous fusions took away.

I have applied this technique to more than ten patients. I have found that the procedure has good results for patients of almost any age group. If a patient has had fusions or failed fusions (where there are nonunions), they are excellent candidates.

I liken this procedure to hip replacement or knee replacement surgery in the sense that if one has a total knee replacement or a total hip replacement that requires revision, surgeons do not come back and fuse hips and knees. They revise with another artificial hip or knee to restore motion and keep the patient active and functional. The same process can apply to the spine, with two important distinctions: Knee and total hip replacement are far more invasive surgeries than artificial disc replacement AND artificial disc replacement is also far more desirable than fusion – in terms of short-term post-op and long-term patient outcome.

Restorative motion surgery, therefore, is not only more beneficial for the patient, but it is rational medical methodology. Moreover, the best part, we have the technology and knowledge necessary to offer to patients today.

Restorative motion surgery adds motion. By adding and restoring motion, we have happier and healthier lifestyles for those people who are living longer. And isn’t that what we all want?