Don’t box yourself in with a forced spinal fusion. Talk to your doctor before it is too late.

I want to tell you a short story about a patient who came to me recently. She was suffering from exquisite pain in her neck. She came into the office, and only 10 minutes into my initial interview, I discovered that she was a case study of what a long-term, untreated cervical herniation can become.

To her, neck pain was an inconvenience. She is a career realtor who specializes in high-end properties, with lots of pressure to service her demanding clients. Clinically though, she was a chronic neck pain sufferer with a ticking timebomb in her neck. The last time she had a doctor take a look at her neck was about twenty years ago with a single x-ray. She received a diagnosis: “mild cervical disc degeneration,” and “mild stenosis.” In other terms, one of her cervical discs had herniated and was impinging on nerves exiting the spinal cord.

She banked on the world “mild” and assumed it meant that with a little care, the herniated disc would heal on its own. Her doctor did the responsible thing and prescribed physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medication. She was “better.” In her own words, she thought she was healed.

What she really experienced was a temporary break in the pain she experienced from a very chronic and ongoing physical condition in her spine. In my medical opinion, based on nearly 30 years as a neurosurgeon, nearly exclusively treating cases of this kind — herniated discs do not heal. I think her doctor also held the same medical opinion. She later told me that her doctor informed her that she might need to look for other treatment later, but I’m fairly positive that he never intended for her to wait quite this long.

It is true that pain symptoms from a herniated disc may subside. It can happen over time, without physical therapy, medication, or even surgery. However, lessening pain may create the illusion that healing has somehow restored the disc. But there is no healing process in the body that can regrow a herniated disc.

When you hear about a disc herniation, I’d like you to think “breakage.” Either by genetics or injury, the annulus (outer disc layer) cracks and allows the pliable center (nucleus pulposus, which has the consistency of crab meat) squeeze through the fracture. Depending on the location of the breakage, disc material may ooze into one of the canals where nerves exit the spinal cord and traverse into the body — pain results when the disc material reaches the nerve root and presses on it. Associated medical terms that you may hear that further describes the condition: “stenosis” and “radiculopathy.”

If you have been diagnosed with a herniated disc, even very severe pain and other symptoms may lessen over time. First, there is a reduction of inflammatory proteins at the location of the herniation. Second, your body may respond to the herniation and reduce the physical size of the herniation through water absorption. Disc material contains a lot of water. I have seen herniations reduced by half or more from natural biological function, which leads me to my incremental treatment approach.

Even as a surgeon, my first recommendation to patients I see in my office in Beverly Hills, CA, often does not include surgery. I will recommend physical therapy. I may suggest nutrition to help bolster the body’s ability to heal. I frequently endorse fitness programs to help strengthen the body. I do all of this to give my patients non-surgical treatment options. However, as with all disc herniations, surgery is nearly always an inevitability. Natural disc mechanics make it so.

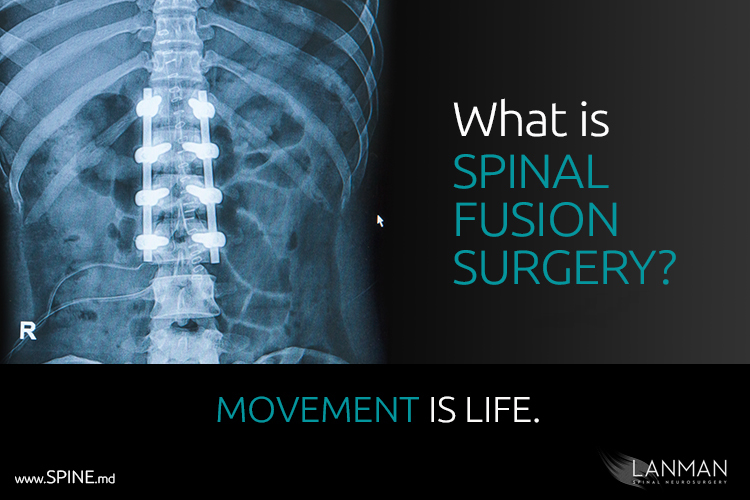

There is no internal biological function that grows more disc material. The annulus cannot heal. Eventually, more disc material will ooze out and trigger additional pain, which may again subside. However, the vertebral interval — the spacing between the bones in the spine — grows smaller, impinging on nerves. Unlike disc material, bones do not readily reduce in size. Once nerves are compressed by bone, they stay compressed until surgical treatment can relieve the pressure. Moreover, left untreated, one herniation can lead to additional herniations in the same way that spinal fusions often leads to adjacent disc failures due to transferred structural pressure in the spine.

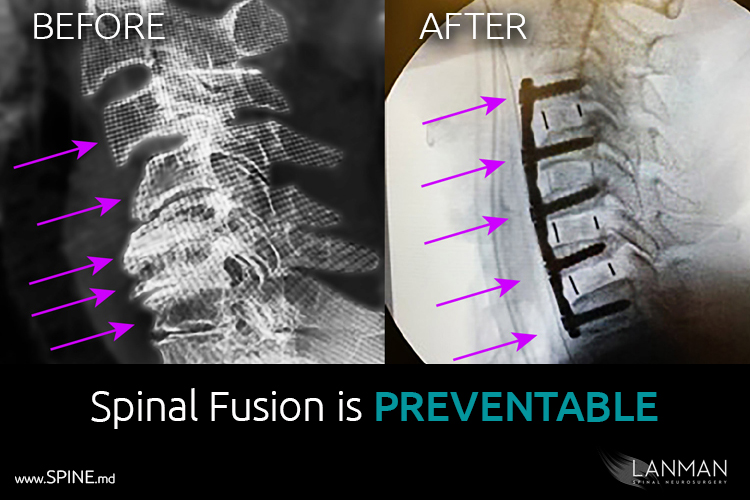

Back to my patient, we ordered a CT scan of her neck. When the images came back, I couldn’t help but wince. Where once there was a single disc herniation, there was now three. Four vertebrae (C7, C6, C5, C4) were fully subluxated. The bones in her neck were in such an altered position that there was pronounced functional loss.

I think that by this time, she knew that her condition was not a simple case. She took the news with very little reaction. In order to stabilize her neck (cervical spine), I recommended a four-level cervical fusion. She was disappointed that artificial disc replacement surgery was out of the question.

It’s not often that I see such a case. No doubt in my mind, had my patient sought medical care even 10 years ago, she may have ended up with three artificial discs and retained the full movement of her neck.

Most of the time, the patient determines treatment options. It takes surprisingly little initiative to avoid additional injury and be far far better than just “better.” They can be greater than better.